You are all at a tavern. It’s a sentence with which the curtain has raised on untold thousands of adventures involving dungeons, or dragons, or both. If you count yourself a fellow traveler—if you’ve ever sat with a twenty-sided die in one hand and a character sheet in the other—it is a collection of sounds probably as familiar to you as a key turning in its lock. And even if you are not the dice rolling sort, we may consider it to be part of our shared cultural heritage and collective unconscious.

Call me Ishmael.

Happy families are all alike.

It was a dark and stormy night.

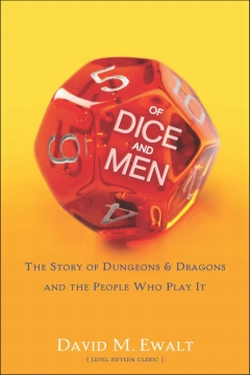

It is thus that David M. Ewalt begins his history and memoir of Dungeons & Dragons, the first, most popular, largest, and most well-known of all table top role playing games—and the entry point for generations of kids and adults who, having been given fire, carried the torch onwards to support an entire industry of D&D’s direct descendants. Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons and Dragons and the People Who Play It opens with a gentle introduction to what D&D is and how it’s played, and to what David Ewalt is when he’s playing it: a twelfth level cleric named Weslocke.

This book twines together two popular strands of nonfiction: the serious history of what was previously low culture—as applied to such formerly ludicrous diversions as comic books and heavy metal—and the tale of the demimonde-joiner—as we’ve seen writers steep themselves in subcultures as fringe as Scrabble and competitive memorization, first on the margins and then more and more intimately, until the outsider becomes the insider, gaining entrance to the holiest of holies and laying eyes upon the relics of the sect.

In this case, the sacred relic we’re talking about is a forty-five year old ping pong table that used to occupy the game room of student and part-time security guard Dave Arneson, who in the early 1970s—along with Gary Gygax, a Wisconsin insurance underwriter turned game developer—built a shared passion for board wargaming into a set of rules and conventions that went on to become the cultural phenomenon known as Dungeons & Dragons.

There are other players in the drama, but the history is really Dave and Gary’s story, as it should be, and it’s the historical parts of the book that shine brightest. While some of Ewalt’s more personal and anecdotal passages feel a little mealy, he writes a business and cultural history as deftly as you would expect from a lauded journalist at Forbes—which, it turns out, he is. The story moves briskly from the game’s prehistory and conceptualization, to its publishing boom and salad days, to its legal troubles and the Satanic panic of the 1980s, through Arneson’s departure and the ultimate downfall of Gary Gygax, and the passing of the game from his control.

The story is easily accessible to the novice, but still carries enough crunch to be engaging to the more familiar reader. I was tickled to find out that the concept of psionics—a kind of psychic wizardry—was added to the game with 1976’s Eldritch Wizardry as a sop to players who hated D&D’s “Vancian” approach to magic—a sort of magic rationing wherein a wizard must prepare spells in advance—and who were more comfortable with a points-based “magic” system like psionics, where the caster could do what they wanted when they wanted, so long as they had enough points to do so. And although reporting that Brian Blume created the Monk character class because he was enamored of the Carl Douglas disco novelty “Kung Fu Fighting” seems a little credulous, the origins of the game are so humble and so deeply personal to a small number of people, that I wouldn’t be surprised if it was true.

Well-written as it is, the history basically ends around 1997 and only briefly resumes with a bit of marketing for D&D Next in 2012. Large chunks of time—specifically the Lorraine Williams and Wizards of the Coast years—are almost entirely omitted. Of Dice and Men is a terrific history of how D&D came to exist, and how it took root and blossomed in its early years. It is not, however, a comprehensive history of the game.

This omission is strange—Ewalt himself notes it at the back of the book—especially in light of how much of the rest of the book, the stuff bracketing the history, feels like filler. Much space is given to in-universe accounts of game sessions Ewalt has played, and I can only imagine these were included to bring unfamiliar readers not just into an abstract game system, but into the game itself, as it is played and experienced. If so, it doesn’t hit the mark quite as it should. In most D&D books, this stuff is referred to as “flavor text,” and even innocent readers know it can be skipped without penalty.

The remainder—Ewalt’s D&D autobiography and his personal musings on the game, his pilgrimage to Gary Con after Gygax’s death—is sprinkled with moments that are well observed and obviously heartfelt, but the balance of it feels unfocused and unfinished, and it is sometimes difficult to tell what it is he is trying to offer a “mainstream audience” (as he describes his ideal reader). The closest he brings you to the thrill of a good game, oddly enough, is in an extended chapter about a definitely-not-Dungeons-&-Dragons LARP weekend he participated in.

The live-action role playing here is doubly interesting because it’s about the only time a woman shows up in the book as an enthusiastic participant, and not a mildly disapproving girlfriend or politely uninterested business acquaintance. I do think that Ewalt believes, as I do, that D&D is for everybody, and that he wrote this book as an honest attempt to bring to everybody what D&D is, and what D&D can be in their lives. But virtually everyone you meet in the book is a white, male, and presumably straight grognard, and while he is conscious enough to take the time to point this imbalance out, he doesn’t explore or even really acknowledge that there might be lots of D&D players who are women, or queer, or not white. A quick glance through the acknowledgments shows that Ewalt talked to an awful lot of people about Dungeons & Dragons, from historical figures to random players at conventions, but female D&D players show up just once, seemingly by coincidence, and he seems to have been content to pursue the matter no further than to express a pleasant surprise at their interest.

But I am, in all fairness, a bit of a grognard myself (French for “grumbler” or “old complaining soldier”), and while Ewalt does entreat such readers to understand the book is aimed at a general audience of nonplayers, he had to know what a hopeless request that was. Grumblers will grumble. It’s not exaggeration or faint praise to say this is the second book I’d reach for if I wanted to expose someone new to the game I love (the first, of course, being the 2nd Edition Player’s Handbook), and I do in fact feel highly motivated to find someone to give this book to. Dungeons & Dragons is about nothing if not being giving of yourself, sharing something exciting with someone across the table, gathering over beer and pretzels and character sheets and opening a book to a page and saying, “Here, look at this.”

We are all at a tavern.

Of Dice and Men is available on August 20 from Scribner.

David Moran knows every dungeon master is only as good as his players. Luckily he’s had some amazing players, and has personally witnessed someone roll a natural 100 with a Rod of Wonder while fighting Zuggtmoy and crowd-surfing on a thousand demons. That really happened.